True Solar Power

Nuclear fusion uses the same process that powers the sun to deliver massive amounts of energy with zero carbon emissions and no accident risk.

-

1 gram of

HYDROGEN ISOTOPES -

11 metric tons of

COAL

A single gram of hydrogen isotopes yields

the same energy as 11 metric tons of coal.

-

1 gram of

HYDROGEN ISOTOPES -

11 metric tons of

COAL

Our sun and every other star is powered by thermonuclear fusion.

When light atoms fuse into heavy atoms under high temperatures, their mass transforms into energy.

Fusion is the ultimate energy source - there is no new source of energy on the horizon after we master fusion.

Learn more about:

-

What is the difference between fusion and fission?

Fission is the process of a heavy atomic nucleus splitting apart into lighter nuclei. Fusion is the process of two light nuclei combining together into a single heavier nuclei. Nuclei heavier than iron can produce energy through fission, and nuclei lighter than iron can produce energy through fusion. This is because iron has the most “stable” and tightly bound nucleus.

While both fission and fusion can release enormous amounts of energy, there are a few key differences:

• Deuterium-tritium fusion releases about 4 times more energy per unit mass than fission

• Fission results in significant radioactivity, as the pieces that the heavy nucleus splits into are highly radioactive. In fusion, no nuclei involved in the process are highly radioactive, though the process can generate very low level radioactivity indirectly through neutron activation.

• Fusion is much harder to make happen, due to the fact that the two fusing nuclei must be given extremely high energy to overcome coulomb repulsion in order to hit and fuse. This typically requires creating and confining plasma at a temperature of 100 million degrees F. Fission, on the other hand, will happen spontaneously if a big enough pile of fissionable material is put together at room temperature.

• Unlike fission, there are millions of years of supply of fusion fuel on earth. -

Can fusion cause a nuclear accident?

A large-scale nuclear accident is not possible in a fusion reactor. The amounts of fuel used in a laser fusion chamber are very small (a few milligrams of fuel at any one time). Furthermore, as the fusion process is difficult to start and keep going, there is no risk of a runaway reaction, and no residual decay heat significant enough to lead to a meltdown of structures.

In Xcimer’s fusion approach, stopping the fusion reaction is as simple as flipping a switch to turn off the laser or target injector. Extensive safety analyses for the Xcimer HYLIFE chamber design demonstrate that even in the case of a worst-case scenario with failure of all confinement systems, the hypothetical maximum dose anyone could receive would be below the annual background radiation dose.

-

Is there any radioactive waste produced in fusion?

There is no radioactive waste by-product from the fusion reaction. Only the fusion chamber components are susceptible to developing low-level radioactivity from neutron exposure. Typically, in fusion, the level of activity that results depends on the structural materials used. Xcimer’s approach utilizing a liquid first wall allows us to use readily available commercial materials that minimize activation, extend the lifetime and comply with our waste and safety goals.

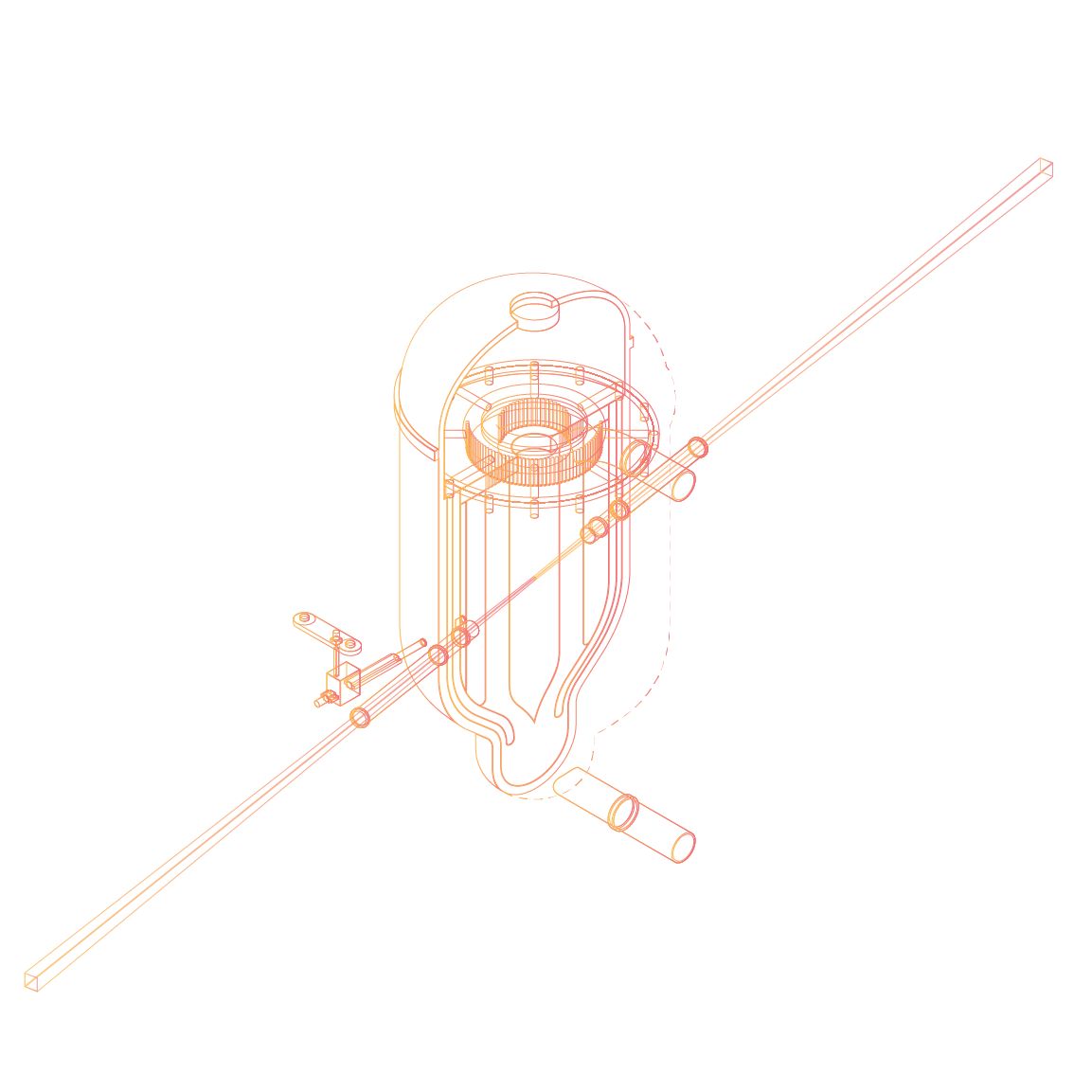

Inertial Fusion Energy (IFE) is an approach that uses lasers to heat, compress and ignite a capsule of fusion fuel. The result is a controlled release of energy that is repeated every few seconds.

An IFE system leverages three components, as shown below:

-

High-Energy Laser

An intense sequence of laser pulses with megajoules of energy converge on the centimeter-sized fusion fuel capsule in billionths of a second.

-

Fuel Capsule

The laser energy generates over 100 million atmospheres of pressure around the fusion fuel capsule, causing it to implode, heat, and ignite.

-

Chamber

Molten salt in the chamber heats as it absorbs the fast burst of fusion energy, and the process is repeated every couple seconds

Lasers create an incredibly intense pulse of light, focused onto a sphere of fuel the size of a pea, creating high temperature and pressure that initiates fusion reactions.

A capsule is ignited every few seconds, only when the laser fires. The generation and release of energy is inherently controlled. The fusion energy from each burning capsule is converted to heat in the chamber walls. A circulating coolant absorbs and carries away the heat to generate steam, which in turn drives turbines to produce electricity. No long-lasting or dangerous radioactive waste is released in the process.

The National Ignition Facility made inertial fusion a reality in 2022.

Governments and universities worldwide have been pursuing fusion energy for 50 years.

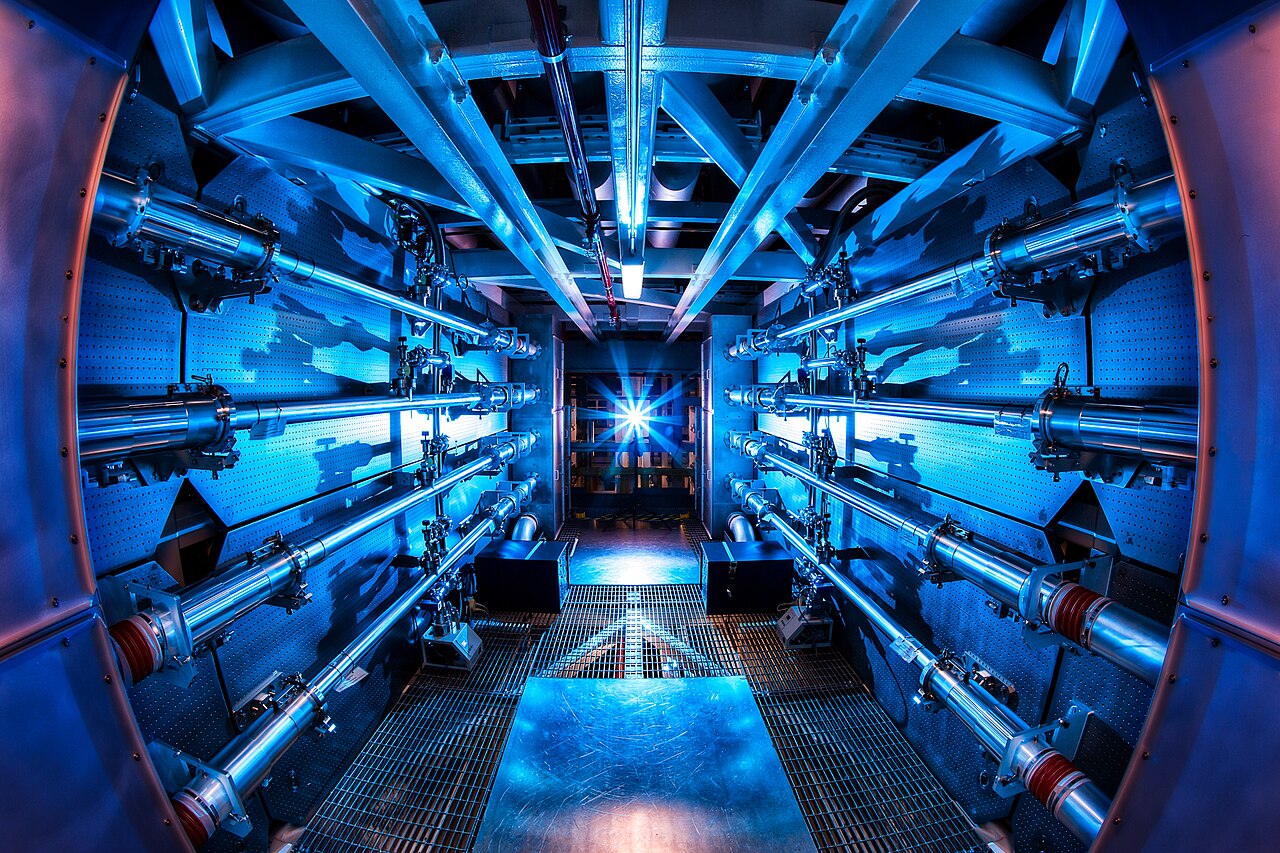

On December 5, 2022, the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Lab performed an experiment in which a 2.05-megajoule laser pulse yielded 3.15 megajoules of fusion energy output. It was the first time fusion scientific breakeven has been achieved in a laboratory.

The challenge: scalability & economics.

NIF’s groundbreaking result was very expensive to achieve, took decades of development, and doesn’t produce enough energy gain for commercial operation. Many obstacles remain to scale this result for commercial use, including the cost of the laser.

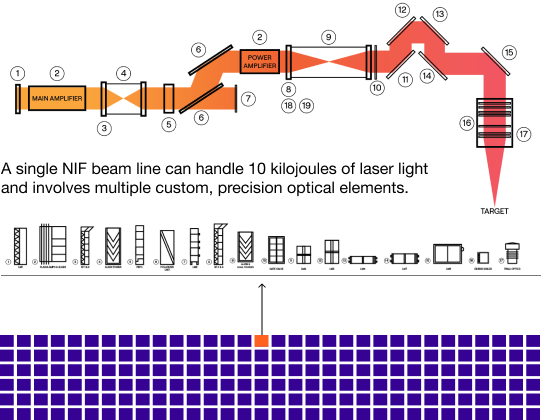

Each of NIF’s beamlines uses a series of precision glass optical elements to generate, control, and precisely direct light towards the target. Because glass can only handle a certain amount of laser energy without being damaged, NIF must spread 2 megajoules of laser energy over 192 independent beamlines, at significant expense.

The entire NIF facility requires 192 beam lines and 120 tons of precision glass, with a total system cost of over $3,600,000,000

-

What exactly has the NIF achieved?

The NIF achieved what is known as scientific breakeven, defined as the fusion energy released from a plasma exceeding the energy that was used to create and heat the plasma. The process of inertial fusion involves shooting a fusion “target” in the center of a large vacuum chamber with a high-energy short laser pulse. The laser energy is ultimately used to compress, heat, and ignite fusion fuel in the target, and the accepted definition of scientific breakeven for inertial fusion is when the fusion burst from the target exceeds the energy of the laser pulse that fires into the chamber toward the target.

To date, the NIF is the only facility that has achieved scientific breakeven in the lab, and the current highest performing shot at the NIF produced 8.6 MJ of fusion energy from a 2 MJ laser pulse, corresponding to a “scientific gain” of 4.13. To date, the next-best performing system is the JET tokamak, which achieved a “scientific gain” of 0.67.

-

Why is the NIF scientific breakeven achievement significant?

To answer this we need to briefly describe a NIF fusion target. A NIF target consists of a heavy metal (such as gold) can about 1 cm in size with a 2 mm diameter spherical fuel capsule situated inside the can. The fuel capsule contains roughly 0.2 milligrams of fusion fuel, as well as a plastic layer on the outside surrounding the fuel. On the NIF, the laser beams do not hit the fuel capsule directly, but instead hit the inside of the can. This creates an intense bath of x-rays that fills the can and heats the plastic layer on the fuel capsule. The plastic layer blows off in billionths of a second creating a compressive force inwards that implodes, heats, and ignites the fusion fuel inside. While the NIF laser delivers 2 MJs of energy to the can, only 250 kJ of energy is actually absorbed by the fuel capsule from the x-rays. The implosion of the capsule can be thought of as a spherical "rocket" with the fusion fuel as the payload, and like a rocket’s efficiency only about 10% of the absorbed energy (~25kJ) ends up in the compressed fuel as heat.

What is significant is that the fuel capsule itself produced 5 MJ of fusion energy when only absorbing 250 kJ of energy. This corresponds to a fuel capsule gain of 20! This gain was possible because a fully ignited and self-sustained burning plasma was produced. This is highly scalable, and up to 10x higher fuel capsule gains can be achieved by imploding a much larger capsule.

-

What is the overall energy gain of the NIF?

Let’s take a look at the overall energy budget of NIF’s highest performing shot to date. 400 MJ were taken from the grid and stored in capacitors to power the laser. The laser produced 2 MJ of optical energy delivered to a NIF “target”, which consists of a fuel capsule about 2 mm in size inside a heavy metal can about 1 cm in size. The laser pulse was delivered to the inside wall of the can, which was heated by the laser to millions of degrees, creating a thermal x-ray bath inside the can. The fuel capsule absorbed roughly 250 kJ of energy from this x-ray bath, causing it to implode, ignite, and burn, releasing 5 MJ of fusion energy. Thus the fuel capsule gain was 20, the target gain (equivalent to the scientific gain) was 2.5, the fuel capsule absorbed 12% of the energy that was in the laser pulse, and the laser efficiency itself was 0.5%. This corresponds to an overall “wall-plug” energy gain of just over 0.01, or 1%.

-

Isn’t the low overall energy gain of the NIF a major challenge to overcome?

A commercial system must have a wall-plug gain of ~10, as opposed to the 1% achieved on the NIF. This might seem like a major gap, but with a much more efficient and energetic laser, it is not as challenging as it might seem. It is important to note that NIF was never designed for efficiency and the laser is based upon technology of the 1990s. The NIF was built for science to support the national security mission of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to help ensure the safety and reliability of the US nuclear deterrent.

In an Xcimer system, we will achieve 10x higher fuel capsule gain by absorbing over 30x more energy into a much larger capsule, we will achieve over 10x higher laser efficiency through the use of excimer lasers, and we’ll couple over 90% of the laser energy directly to the fuel capsule, vs. only 12% coupled via the x-ray bath on the NIF. These together provide a 1000x increase in wall-plug gain compared to the NIF, allowing for a commercially viable system.

-

Why can’t the NIF laser be scaled for Inertial Fusion Energy?

While the NIF has made an amazing achievement, there are several significant challenges in making the laser system commercially viable.

• The laser technology is far too expensive to scale to 10 MJ, which is the energy level needed for robust fusion target operation. The NIF contains over 120 tons of high quality laser glass, as well as over 4000 square meters of optical surfaces to direct the laser beams to a target. This large volume of precision optical material contributed a significant amount to NIF’s $3.5B cost.

• The NIF can only shoot a few times a day, vs a shot every few seconds. Even at 2 MJs of energy, the NIF experiences a significant amount of damage to its optics on every shot - over $40M per year is spent on refurbishment of the optics. Going to 1 shot every few seconds would simply be unaffordable.

• The NIF has 192 beams and 30 square meters of final optical area. This high number of penetrations and large final optical area exposed to the target make it infeasible to use a coolant as a liquid wall to protect the reactor chamber.While there have been significant advancements in solid-state laser technology since the NIF was built, solid-state glass systems are still very expensive, not scalable to 10 MJ, and must still use a large number of laser beams to hit a target.

We are building on over 100 years of science and decades of fusion development.

This timeline presents pivotal milestones, tracing the journey of fusion energy from the early 20th century’s experiments and foundations, to the 2022 landmark of net energy gain at NIF.

They mark key innovations, advancements and partnerships that led to the development of Xcimer’s IFE system.

In 1926 Arthur Eddington proposed that stars

produce energy from hydrogen fusion.

-

1939

Hans Bethe Develops Theory for the Sun’s Fusion Fuel Cycle

For over a century it was not known how the sun could maintain its temperature and energy output for the billions of years that geologists knew the earth had been in existence. In 1939, Hanz Bethe finally discovered the nuclear fusion cycle that powers the sun, which involves proton-proton fusion.

-

1952

Ivy Mike, First Fusion Test

Los Alamos Laboratory

The idea of using fusion in a weapon dates back as early as the Manhattan project, and was developed primarily by Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam. Their concept was to use the x-ray energy produced by an atomic fission device to flow over to a physically separate fusion component and implode and ignite this separate component. This worked on the very first try in the Ivy Mike test of 1952, which yielded 10 megatons of energy. The fusion plasma was inertially confined and produced enormous fusion gain. The physical principle of high-gain inertial confinement fusion was conclusively demonstrated here.

-

1960

Laser is Invented

Hughes Research Laboratory

Theodore Maiman operated the first laser on May 16th 1960 at Hughes Research Laboratory using flashlamps and a ruby rod. The initial paper was rejected by Physical Review Letters, but was subsequently published in Nature.

-

1962

Laser Inertial Fusion is Put Forward

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Shortly after the laser was invented, scientists realized a laser could be used to provide the temperatures and pressures needed to implode and ignite fusion fuel, without needing an atomic fission bomb. The major difference, however, was that the laser energy available was many orders of magnitude less than what could be provided by a fission bomb, and this led to many challenges.

-

1972

John Nuckolls 1972 Paper

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Nuckolls’ seminal paper in the field of inertial fusion proposed using a laser pulse shaped precisely in time to implode DT fuel and achieve densities 10,000 times solid. It was estimated that if this could be achieved, then ignition could be achieved with only 1 kJ of laser energy. While this turned out to be impossible due to hydrodynamic instabilities and nonlinear laser plasma interaction issues, it began investigation into laser-driven inertial fusion in earnest.

-

1975

HYLIFE-I Chamber is Proposed

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

The High Yield Lithium Injection Fusion Energy (HYLIFE) chamber was the first proposal put forward by Livermore for how to contain sequential fusion bursts and convert the energy into heat to drive a steam cycle. The concept utilized two opposing beams to illuminate a sequence of fusion targets at a repetition rate of once per second inside a waterfall of lithium contained in a steel chamber. The lithium would contain gigajoule fusion bursts and protect the steel chamber from all ions, target debris, and 14 MeV neutrons. Xcimer’s approach is largely based around this original concept.

-

1977

Shiva Laser Built at LLNL for Laser Fusion Research

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

The Shiva laser was a 10 kJ system at 1 micron wavelength. It was the largest laser in the world at the time, and was built to better understand the coupling of laser energy to a fusion target as well as target implosions. A major result was the discovery of the need to move to shorter wavelengths due to laser plasma interactions inhibiting effective coupling of laser energy to targets.

-

1970s

Various Excimer Lasers are Developed

The first excimer laser was built at Livermore by Paul Hoff in 1972, and by the late 70s many more excimers had been discovered, including argon fluoride and krypton fluoride. Much of the gas chemistry of these lasers had been worked out by the end of the decade, with several kJ-scale systems built.

-

1984

Nova laser completed

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

The Nova laser was built after lessons learned on Shiva, and could hit a target with a 45 kJ laser pulse at a much shorter wavelength of 351 nm. Ignition was expected, but it was more difficult to achieve the needed high-compression implosions than originally thought (the lower the laser energy, the higher the compression of the fuel capsule that is needed). Nevertheless, Nova significantly advanced the science of inertial fusion, and paved the way for the NIF.

-

1986

Halite Centurion tests demonstrate High-Gain Inertial Fusion

A series of underground nuclear tests were fielded to lay to rest the viability of imploding and igniting laboratory scale fusion fuel capsules. These capsules were driven by siphoning a very small amount of x-ray energy from adjacent nuclear detonations, and they achieved ignition and high gain. Detailed reports are classified, but these tests conclusively demonstrated inertial fusion energy is possible with a high-enough energy laser.

-

1986

NAS Review Recommendation to Build 10 MJ Laser

National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences held a review of inertial fusion in 1986, after analysis of all data to date from both laser fusion facilities as well as the Halite Centurion tests. The committee recommended the construction of a 10 MJ laser to ensure robust fusion ignition and high gain.

-

1995

National Ignition Facility Project Starts

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

The National Ignition Facility was sold to Congress with a laser energy of 2 MJ, significantly short of the 10 MJ level recommended by the NAS. The 2 MJ system was a compromise, as a 10 MJ system with then-proposed technologies would have been far too expensive.

-

2010

Efficient, repetitively pulsed excimer laser for IFE demonstrated

NRL

During the High Average Power Laser (HAPL) program, the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) significantly advanced excimer laser technology for inertial fusion energy. In particular, the kJ-scale Electra laser operated repetitively at five shots per second for up to a day at a time, demonstrating key technology necessary for enabling an excimer laser to continuously shoot fusion fuel capsules in a power plant.

-

2022

Breakeven Achieved at the NIF

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

In 2022, the NIF achieved scientific breakeven, with the fusion burst from a fusion target exceeding the total laser energy delivered to the target. Since then, the NIF has improved over this result, with 5 MJ of fusion energy produced from a 2 MJ laser pulse. The significance of this result is the production of a fully ignited and burning plasma, with a fuel capsule gain of 20. The data from the NIF fully supports the original 1986 NAS conclusion that a 10 MJ would allow for robust ignition and high gain.